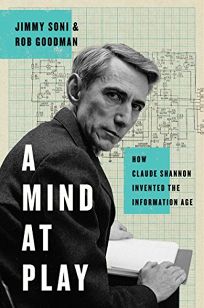

There’s a new biography of Claude Shannon out: A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age, by Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman. Shannon well deserves a popular biography and much greater renown, but I was disappointed by both the book and Shannon himself.

Shannon’s work is fundamental to everything about technology today. In his master’s thesis (!) he set out how to implement Boolean logic with electrical switches and circuits. I didn’t know it was Shannon who’d figured this out: I just sort of assumed it had always been known.

Later, in a 1948 paper, after war work where he once had a quiet lunch with Alan Turing, Shannon invented information theory. As Wikipedia says, information theory’s “impact has been crucial to the success of the Voyager missions to deep space, the invention of the compact disc, the feasibility of mobile phones, the development of the Internet, the study of linguistics and of human perception, the understanding of black holes, and numerous other fields.” The internet, black holes, human language—that’s a huge variety! But it’s true, information theory is now behind all of that.

However, the book doesn’t do full justice to information theory and its effects, or to Shannon’s work overall. Soni and Goodman (not experts in the field) do a capable job of explaining what Shannon did, but ultimately fail to get across its full import.

My colleague John Dupuis reminded me of Siobhan Roberts’s two excellent biographies of mathematicians: H.S.M Coxeter (King of Infinite Space: Donald Coxeter, the Man Who Saved Geometry) and John Conway (I reviewed Genius at Play: The Curious Mind of John Conway in 2015). Their work is mostly very abstract—multidimensional geometric figures or the Monster group)—but Roberts does an excellent job of explaining it all and why it’s important.

Roberts does an equally good job of describing her subjects. Coxeter was a cold man, and Conway is a bit bonkers. You come away from her biographies knowing those men, but you don’t finish A Mind at Play feeling the same about Shannon.

There’s another problem with the book, which is really a problem with Shannon: he gave up. He did an amazing body of important work, then he drifted away and spent the rest of his life fiddling and tinkering. Soni and Goodman make as much of this as they can, but really, he gave up.

In 1957 Shannon moved from Bell Labs to MIT.

Even at MIT, Shannon bent his work around his hobbies and enthusiasms. “Although he continued to supervise students, he was not really a co-worker, in the normal sense of the term, as he always seemed to maintain a degree of distance form his fellow associates,” wrote one fellow faculty member. With no particular academic ambitions, Shannon felt little pressure to publish academic papers. He grew a beard, began running every day, and stepped up his tinkering.

What resulted were some of Shannon’s most creative and whimsical endeavors: … the trumpet that shot fire out of its bell when played … the handmade unicycles … a machine that solved Rubik’s cubes …

That’s all nice, but he was a full professor at MIT, and that carries responsibilities. He barely did any teaching, didn’t supervise many graduate students, didn’t get involved in the operations of the university, didn’t get involved in the world.

Yet Shannon had also come to accept that his own best days were behind him…. Henry Pollak recalls visiting Shannon at home in Winchester to bring him up to date on a new development in communications science. “I started telling him about it, and for a brief time he got quite enthused about this. And then he said, ‘Nuh-uh, I don’t want to think. I don’t want to think that much anymore.’ It was the beginning of the end in his case, I think. He just—he turned himself off.”

That’s sad.

The previous book Soni and Goodman did was a biography of Cato the Younger, the Roman philosopher, senator and general. It’s similar in that Cato deserved a popular biography but I still hope for a better one. It’s strikingly different, however, in the natures of the two men: Cato never gave up. He stood up his entire life for what he believed in, even when it meant he was one of the leaders in the fight against Julius Caesar, who was taking over the Roman Republic. Caesar won, of course, and Cato committed suicide, which might seem like giving up, but to Stoics is a reasonable action to take when one would rather control one’s own end then live under the rule of a tyrant.

Coxeter never gave up. John Conway never gave up. Richard Feynman never gave up. The great ones never give up. But Shannon gave up.

Miskatonic University Press

Miskatonic University Press